The Crucial Role of Mouse Poop in HIV Research (Advanced Read)

Miranda Bie (edited by Kanza Mirza, Liam Quartermain)

Posted on 10 Oct, 2020

Introduction to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Diligently working in the Ostrowski Lab at the University of Toronto is a student pipetting an odourless clear liquid (mysteriously labelled PMSF) into a very much odorous tube of mouse feces. Although seemingly small and insignificant, if not downright gross, that piece of stool might pave the way for the eradication of HIV.

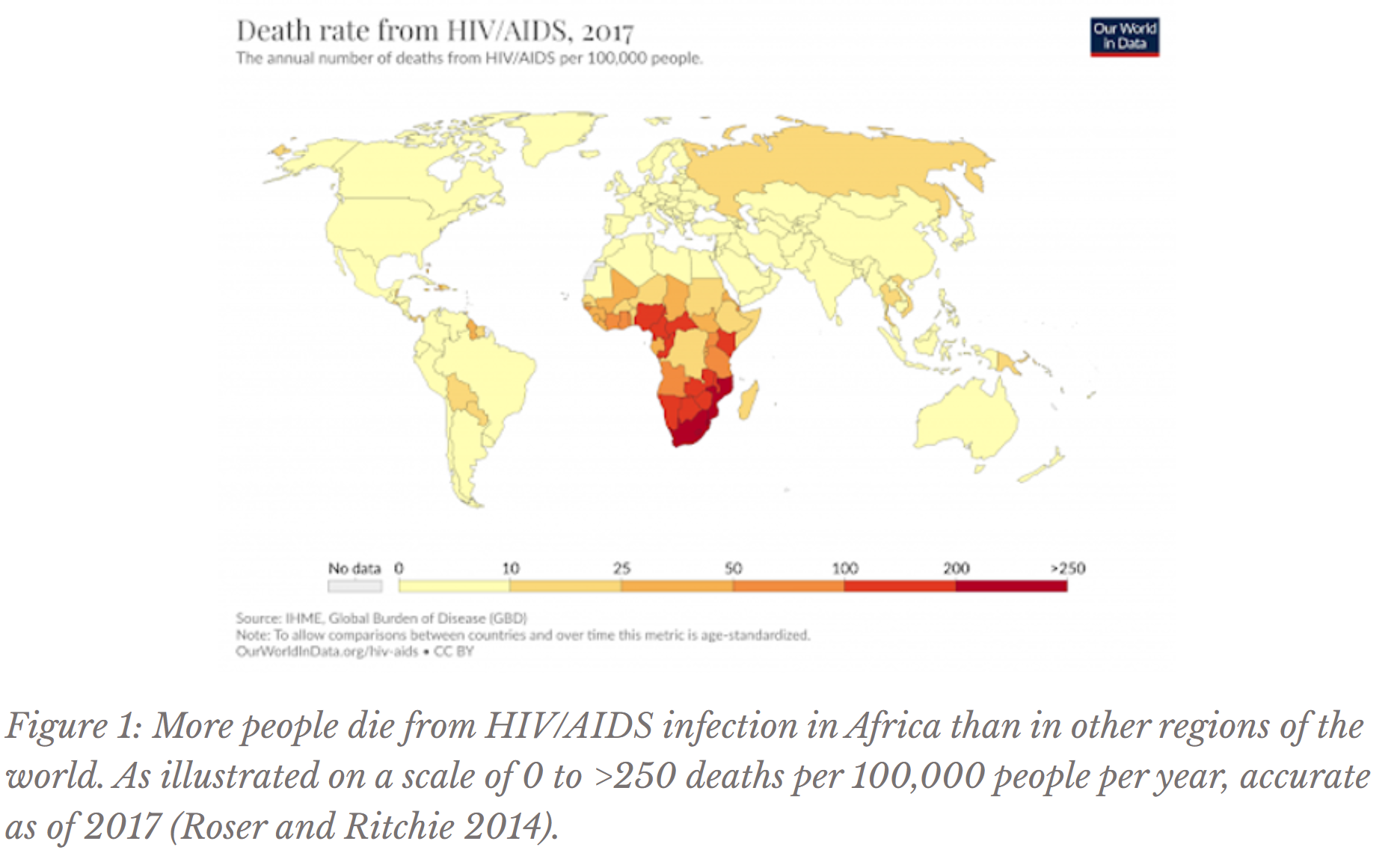

Thanks to the development of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV patients can live a relatively long and healthy life without developing AIDS. However, the majority of infected individuals live in Africa, where low incomes often impede access to expensive, lifelong drug regimens (HIV/AIDS ... 2019, Figure 1). A vaccine to eradicate this disease, the current subject of investigation by the UofT mouse feces student, would eradicate ART’s issue of long-term affordability. Vaccines contain epitopes (non-infectious protein particles from the virus’s surface) to essentially teach the body’s immune system to recognize the virus and produce antibodies, or molecules that target a pathogen for elimination. Thus, vaccines elicit antibody production so that if the body ever encounters HIV again, the virus will be eliminated before disease symptoms arise.

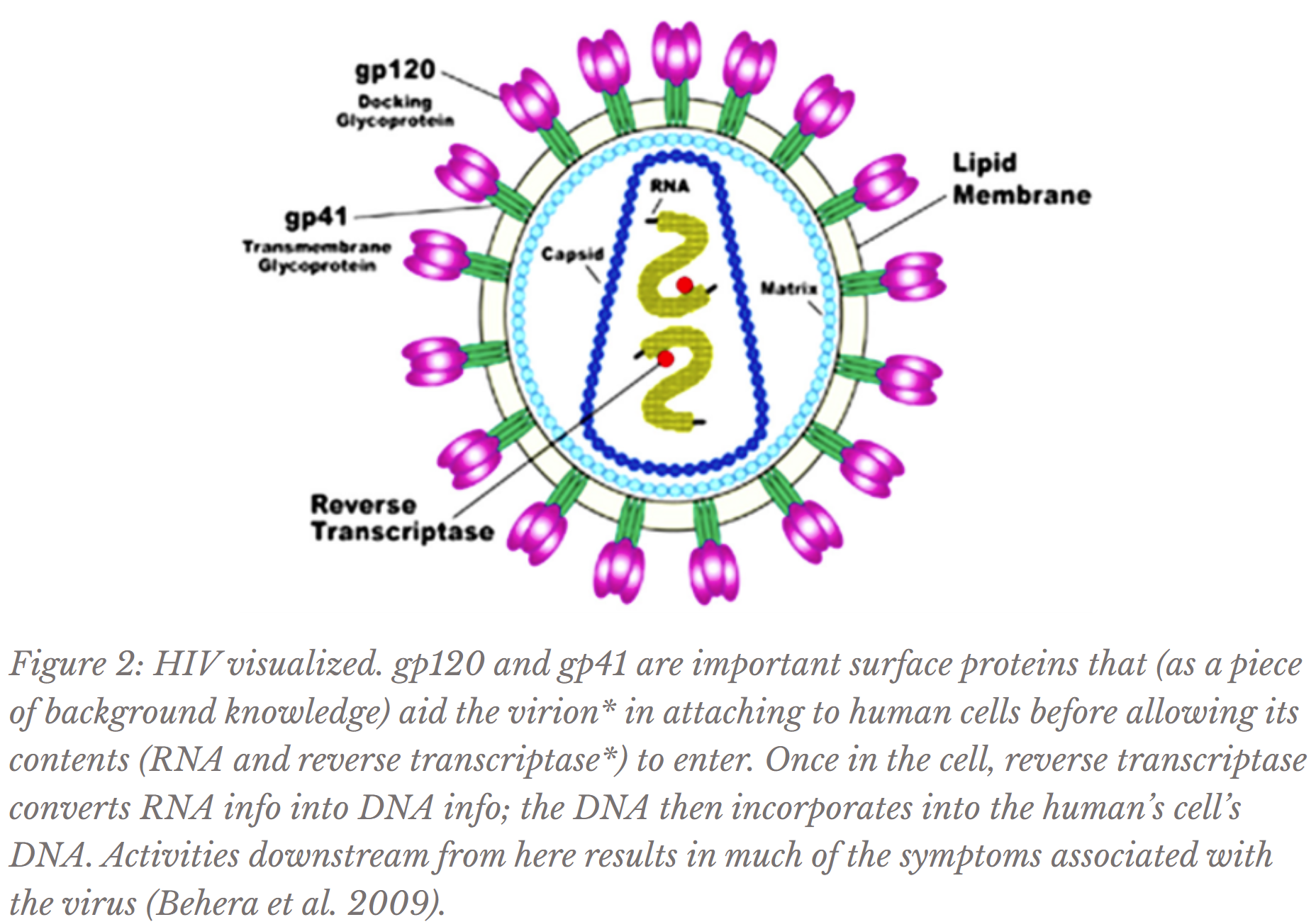

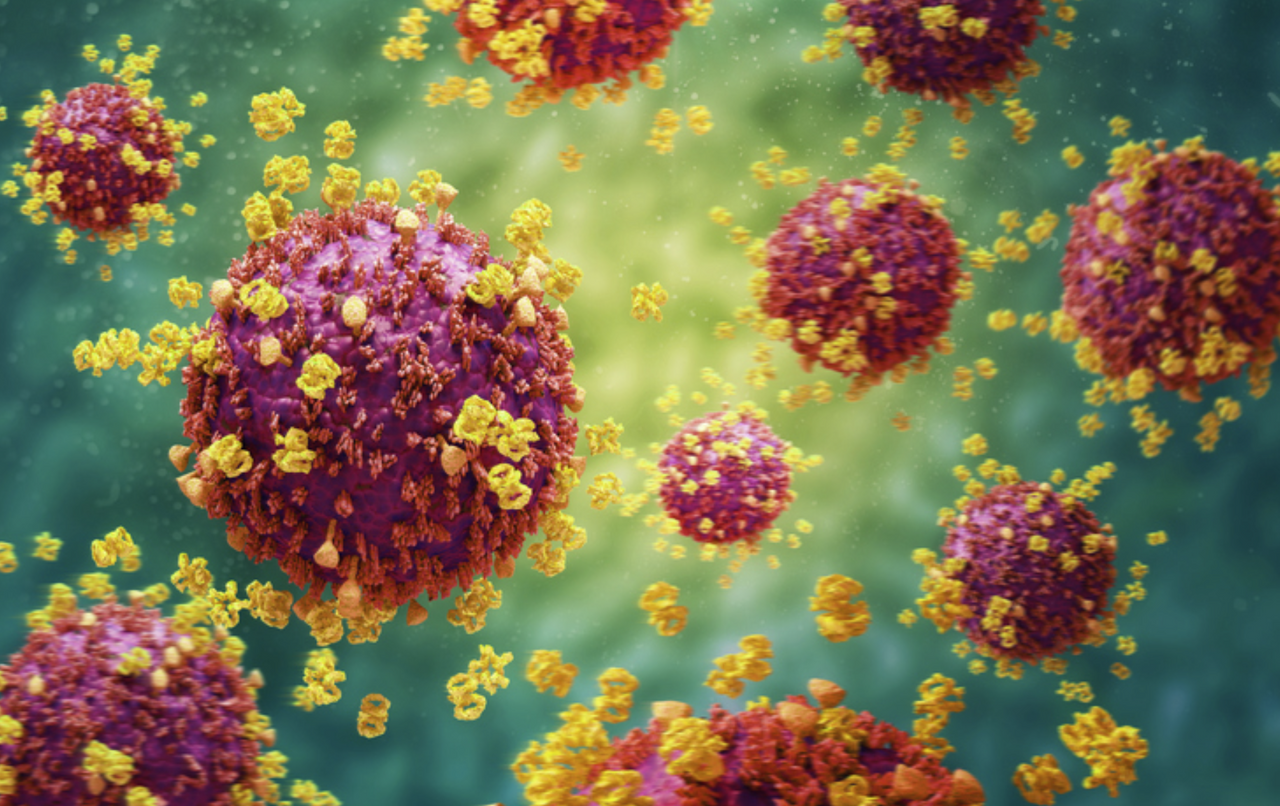

However, the search for an HIV vaccine is not unique to the Ostrowski Lab; in fact, this endeavor has occupied the careers of countless accomplished, hopeful scientists since the start of the global AIDS epidemic, but still no marketable vaccine exists due to several factors. One major reason is that HIV mutates quickly, at a rate rarely exceeded by even other viruses (Cuevas et al. 2015). This high mutation rate means that its surface appearance changes too quickly for the immune system to reliably recognize (refer to Figure 2 for HIV’s surface proteins). Therefore, exposing the body to one type (or strain) of HIV would not necessarily prepare the immune system for future encounters with a mutated form of the virus. Additionally, the conserved regions* of HIV, or the parts of the virus that do not often change appearance, are often protected or hidden by highly mutable parts of the virus that protrude (Burton and Hangartner 2016). Therefore, decades of dedicated research has still not revealed a vaccine that would elicit effective antibody production.

Research on HIV at the University of Toronto

The Ostrowski Lab at the University of Toronto investigates yet another facet of vaccine-creation by researching biological compounds that increase the sheer amount of antibody production elicited by a vaccine. Tumour necrosis factor superfamily (TNFSF) molecules are known to strengthen antibody responses. In particular, the lab researches antibody response to three TNFSFs (APRIL, BAFF, and CD40L). Each molecule enhances the production and efficacy of antibodies through different pathways (as Jun et al. 2020 further explains). In particular, the Ostrowski Lab determines whether these TNFSFs can enhance HIV-specific antibody response.

To do so, the molecule used for inducing antibody production is gp140*. Using Figure 2 as a reference, gp140 is used by scientists to mimic as closely as possible in appearance gp120 connected to gp41, which are key HIV surface proteins comprising a “spike,” with gp120 on the top connected to gp41 on the bottom (Harris et al. 2011). Thus, when added to a vaccine, gp140 triggers immune system defense against HIV surface-like molecules so that when exposed to the actual virus in the future, the body already knows to produce antibodies targeting gp120 and gp41. Why is the gp120:gp41 spike itself not used in a vaccine? The actual HIV spike is not stable in a soluble (water-based) vaccine; gp120 will separate from gp41 when the spike is removed from the virion, so when introduced to the body, the immune system will not learn to produce antibodies responding to a structurally accurate protein (Kovacs et al. 2014).

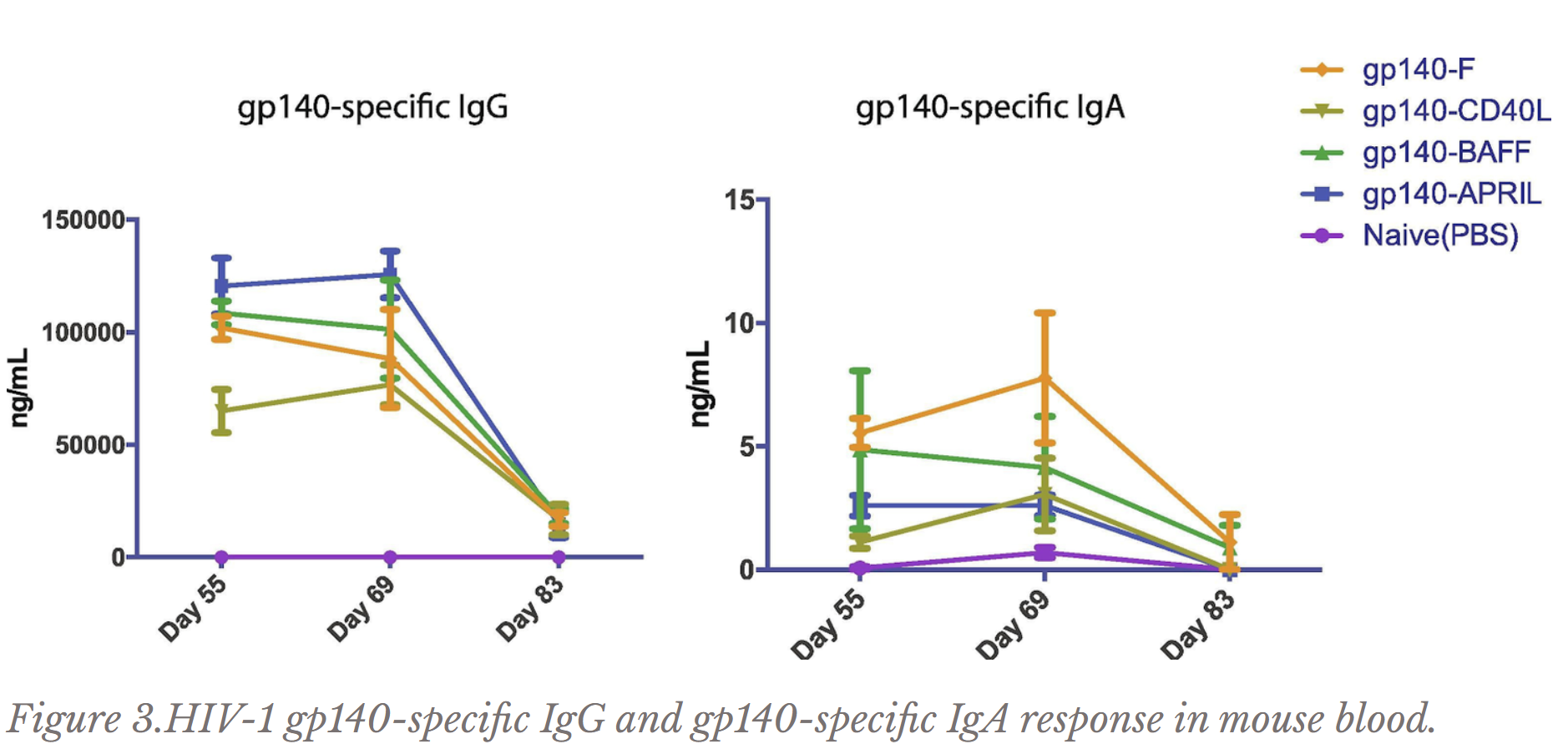

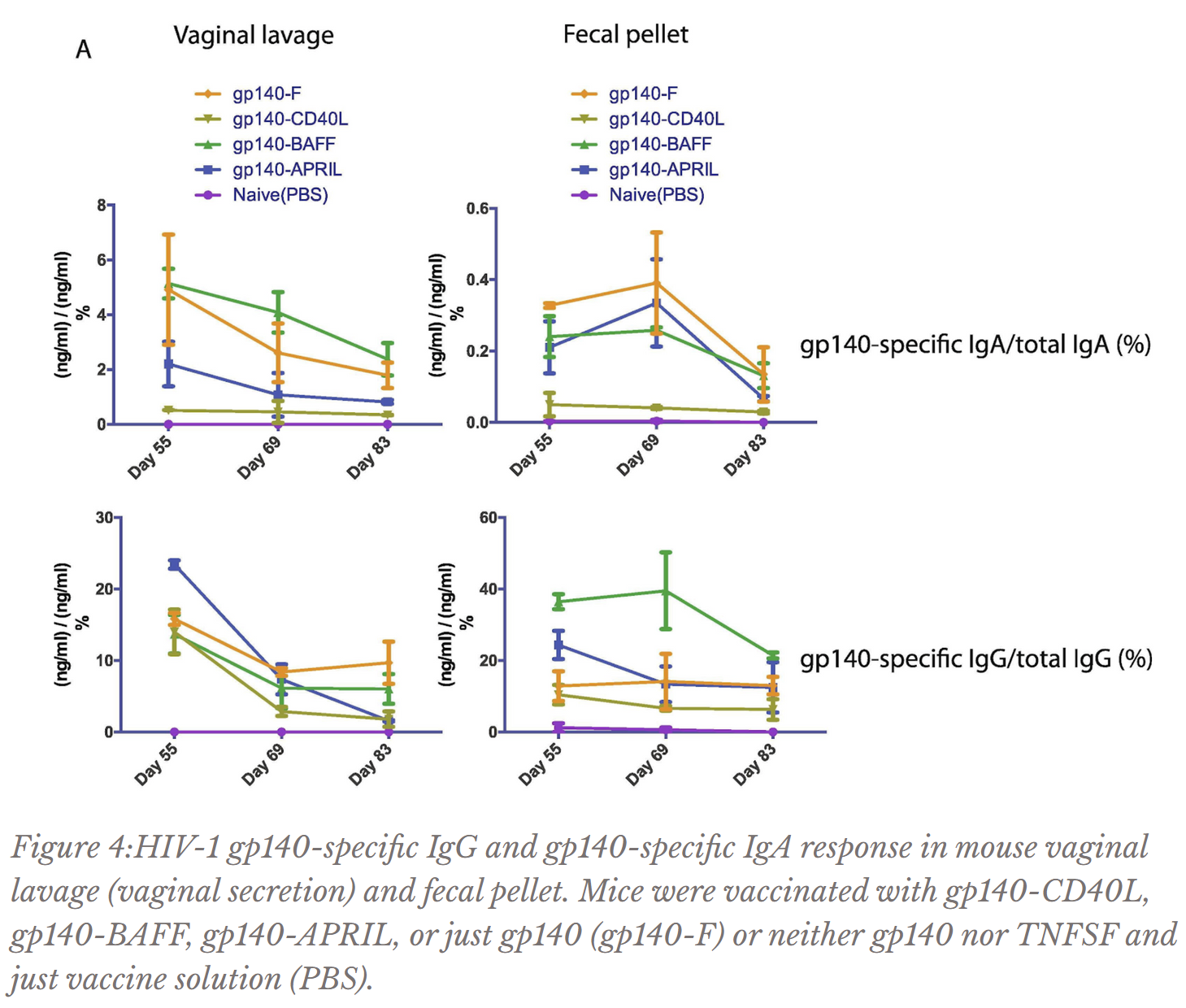

To test whether TNFSFs increase effective antibody production, each TNFSF was fused or attached to gp140. The gp140-TNFSF fusion was tested on a mouse model through a vaccination regimen lasting 83 days. Antibody concentrations from mouse blood, feces, and vaginal secretions of mice receiving the full gp140-TNFSF vaccine were measured (Figures 2 and 3) and compared with mice that received just gp140 (triggering antibody production targeting HIV, but without the TNFSF molecule) or mice that received neither gp140 nor TNFSF (essentially receiving a needle injection but not the functional contents of the vaccine). If TNFSFs indeed increase effective antibody production, the gp140-TNFSF fusion should induce more effective antibody production than gp140 alone. If the experiment was conducted correctly, mice receiving neither gp140 nor TNFSF should not be producing antibodies targeting gp140 because the body does not randomly produce antibodies without first being exposed to the viral protein.

Two forms of antibodies (named IgA* and IgG*) with previously known HIV-targeting properties were investigated by the UofT Ostrowski Lab. IgA is mostly found in mucous layers (gut, bodily secretions) to defend against pathogens there and IgG is most commonly in the blood. From previous knowledge, gp140-specific IgA and IgG antibodies found in the blood, feces, or vaginal secretions increase immune defense, except for gp140-specific IgA in the blood. In fact, gp140-specific IgA in blood is actually associated with a decreased ability of the immune system to mount an attack against HIV (Haynes et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2020).

The Ostrowski Lab discovered that for mouse blood, all gp140-TNFSF fusions induced less gp140-specific IgA production than just gp140 alone (Figure 3); as gp140-specific IgA in the blood is actually detrimental towards defense against HIV, this piece of data bodes well for the gp140-TNFSF fusion. Due to the closeness of values for gp140-specific IgA in vaginal secretions and fecal pellets and for gp140-specific IgG in vaginal secretions (Figure 4) and blood (Figure 3), not much can be concluded from the data. However, gp140-APRIL and especially gp140-BAFF vaccinations induced higher concentrations of gp140-specific IgG in mouse feces than just gp140 alone (Figure 4); as aforementioned, more gp140-specific IgG has been associated with greater defense against the virus.

Mice were vaccinated with gp140-CD40L, gp140-BAFF, gp140-APRIL, or just gp140 (gp140-F) or neither gp140 nor TNFSF and just vaccine solution (PBS).

The Ostrowski Lab’s experiments do not present conclusive findings on the efficacy of TNFSF in boosting antibody response to gp140. However, the results strongly suggest that gp140-BAFF and, to a lesser degree, gp140-APRIL in particular could increase desirable antibody production. Not discussed in this paper is the lab’s research results detailing that BAFF and APRIL can also increase the longevity and effectiveness of B cells*, or cells responsible for releasing antibodies. This excerpt of preliminary results suggest that continuation of TNFSF research with respect to eliciting antibody response will greatly aid the global effort towards developing an HIV vaccine.

Due to the obstacles aforementioned preventing the fast discovery of an HIV vaccine, even some of the most brilliant scholars are losing hope in ever witnessing the eradication of HIV (Wilson and Watkins 2009). However, HIV is not the only disease to witness obstacles in the way of developing a viable vaccine. Rarely is the journey smooth and straightforward. Upon its clinical trials in the 1950s, the polio vaccine faced criticism for its side effects of paralysis or even death upon administration. However, scientists persevered until an oral vaccine without these side effects was discovered (Meldrum 1998) and today we use injection vaccine furthermore developed with the risk of virtually no side effects (Polio ... 2018). As a result of the modern, highly effective polio vaccine, no cases of polio exist in Europe or the Americas today, but scientists across the world had devoted decades of painstaking research to achieve this. So kudos to the poop-handling students at the University of Toronto for not giving up hope just yet.

Glossary: Abbreviations and terms

- AIDS: acquired immune deficiency syndrome; once developed (from initial HIV contraction several years ago), immune function is severely compromised, usually resulting in death from complications

- APRIL: a proliferation-inducing ligand, for bone marrow plasma and mucosal cell survival; for antibody switching to IgA

- ART: antiretroviral therapy, drug regimen for slowing down virus growth; often many such medications taken in combination for optimal viral suppression (highly active antiretroviral therapy, HAART)

- B cells: immune cells that release antibodies into the body

- BAFF: B cell activating factor, for bolstering B cell (which produce antibodies) survival; for antibody switching to IgA

- bNAbs: broadly neutralizing antibodies, antibodies produced in the host (receiving the vaccine) elicited by the vaccine to target conserved regions across many virus types over evolutionary time; such antibodies function to neutralize the pathogen, or eliminate viral functions

- CD40L: CD40 ligand, for B cell (which produce antibodies) propagation, survival, switching to IgA, and development of greater strength of antibody binding to pathogen

- Conserved regions: parts of viral genome and its associated protein products that remain consistent across many different types of the virus, despite the high mutation rate of viral genome

- Env: an HIV surface protein required for viral entry into human cells easily recognized by antibodies produced by the body in defense against HIV

- gp140: a protein developed by researchers to mimic the amino acid sequence and structure of Env for use in vaccines because Env once removed from HIV surface no longer retains its shape

- HIV: human immunodeficiency virus, once contracted, debilitates immune function over time and progresses into AIDS without treatment

- IgA: an antibody class most often found in mucosal membranes for defending against pathogens

- IgG: an antibody class most often found in blood for defending against pathogens

- PMSF: phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, for destroying bacterial cells

- reverse transcriptase: (roughly) an HIV protein responsible for translating RNA information into DNA information

- TNFSF: tumour necrosis factor superfamily, molecules involved in B cell (which produce antibodies) survival and propagation

- virion: the complete form of a virus existing outside of a host cell, before infection (Figure 2)

References

Behera PM, Sethi BK, Behera KK, Pani D, Sahoo S, Padhy S. 2009. Computational analysis of POL gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. [accessed 2020 Jul 18];37(2):264-269. https:// www.notulaebotanicae.ro/index.php/nbha/article/view/3437 doi:10.15835/nbha3723437.

Burton DR, Hangartner L. 2016. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV and their role in vaccine design. Annual Review of Immunology. [accessed 2020 Jul 18];20(34):635-659. https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27168247/ doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055515.

Cuevas JM, Geller R, Garijo R, López-Aldeguer J, Sanjuán R. 2015. Extremely high mutation rate of HIV-1 in Vivo. PLoS Biology. [accessed 2020 May 18];13(9). https:// journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio 1002251 doi:10.1371/ journal.pbio.1002251.

Harris A, Borgnia MJ, Shi D, Bartesaghi A, He H, Pejchal R, Kang Y, Depetris R, Marozsan AJ, Sanders RW, et al. 2011. Trimeric HIV-1 glycoprotein gp140 immunogens and native HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins display the same closed and open quaternary molecular architectures. PNAS. [accessed 2020 Jul 18];108(28):11440-11445. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ 21709254/ doi:10.1073/pnas.1101414108.

Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, Evans DT, Montefiori DC, Karnasuta C, Sutthent R, et al. 2012. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. New England Journal of Medicine. [accessed 2020 Jul 18];366:1275-1286. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa1113425 doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1113425.

HIV/AIDS: Key facts. 2019 Nov 15. World Health Organization. [accessed 2020 May 18]. https://www.who.int/ news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids

Liu J, Clayton K, Gao W, Li Y, Zealey C, Budylowski P, Schwartz J, Yue FY, Bie Y, Rini J, et al. 2020. Trimeric HIV-1 gp140 fused with APRIL, BAFF, and CD40L on the mucosal gp140-specific antibody responses in mice. Vaccine. [accessed 18 Jul 2020];38(9):2149-2159. https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32014267/ doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.050.

Kovacs JM, Noeldeke E, Ha HJ, Peng H, Rits-Volloch S, Harrison SC, Chen B. 2014. Stable, uncleaved HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp140 forms a tightly folded trimer with a native-like structure. PNAS. [accessed 18 Jul 2020];111(52): 8542-18547. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC4284565/ doi:10.1073/pnas.1422269112.

Meldrum M. 1998. “A calculated risk”: The Salk polio vaccine field trials of 1954. British Medical Journal. [accessed 19 Jul 2020];317(7167):1233-1236. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ 9794869/ doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1233.

Polio Vaccine. 2018, July 12. HealthLink BC. [accessed 2020 May 19] https:// www.healthlinkbc.ca/medications/zb1200

Roser M, Ritchie H. c2014. HIV/AIDS. Our World in Data. [updated 2019 Nov; accessed 2020 May 18]. https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids#citation

Wilson NA, Watkins DI. 2009. Is an HIV vaccine possible? The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. [accessed 19 Jul 2020];13(4):304-310. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2893404/ PMCID:PMC2893404.